Rifle Brass Lifespan

One of the errors that reloaders frequently make is using their brass either too little, or more commonly, too long before they toss it out. The latter mistake often leads to issues that can end an otherwise enjoyable day at the range. I often see people ask online, "how many loads are you getting on ______ caliber of rifle brass,” hoping that if the response is "x" number, then they can feel safe and expect about the same number of reloads on their own rifle brass. Of course the answer is never that straightforward. There are many variables that factor into determining the number of reloads you can get from a single piece of rifle brass, and I will get into those momentarily, but in short the number of times that “some guy on the internet" is able to reload his own rifle brass has little to no relationship to the number of times you can or should reload your own.

How do you know when it is no longer safe to reload a piece of rifle brass?

There are four parts of a cartridge that can indicate when a brass casing is has reached its safe lifespan; the rim, the walls, the primer pocket and the neck. One extremely important part of reloading is case inspection. You should always closely inspect your cases prior to each loading in order to catch any pieces that may be worn-out or damaged. Here are the things to look for, the simplest of which can be caught with a visual inspection:

1) Case necks - Are the necks in good condition? Are any split, possessing ragged edges or are otherwise damaged?

2) Case rims - Are any broken, chipped or otherwise damaged?

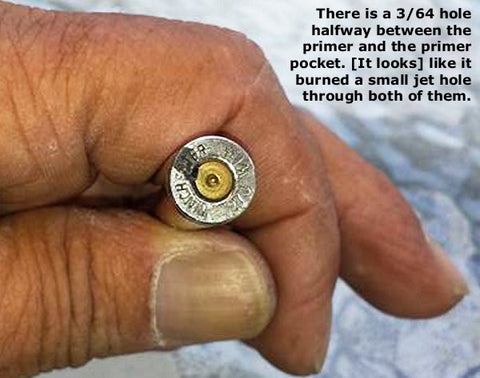

3) Primer pockets - Are all of the primers still in the fired brass? Are any of them loose and/or moving in the pocket? When you are seating a new primer does it go in too easily? Are there signs of escaping gas?

And last but not least...

4) Case walls - This one requires a bit more than a casual, visual inspection, but is often the one that bites people the hardest. After a certain number of firings the brass case stretches (and of course we then trim them to the proper length). Externally the piece of brass may look fine and no different than any other piece of brass, but internally a thin spot in the case wall could be developing which can lead to case head separation. This will likely result in a ruptured case lodged in your rifle chamber. The simplest way to detect this is with what is known as the "paperclip method." This involves running a bent paperclip along the inside of the case and feeling for a ridge. I do this with every piece of rifle brass, every time I load it.

Examples of partial case head separation.

What variables determine how long a piece of rifle brass may last?

There are many factors that play a part in determining the number of reloads you can obtain from a piece of rifle brass. These include the quality of brass, the caliber, how "hot" the rounds are loaded, the type of sizing dies used, primer pocket preparation (or lack thereof), whether or not the brass is annealed, and even chamber specs....basically anything that affects the pressure inside the cartridge.

Here is a brief review of these factors (for additional information feel free to leave questions in the comments section below):

- Some brass cases are softer than others, meaning that the brass and or primer pockets deform more easily than other brands of brass when fired with the same charge. As an example, Lapua Brass is considered by many to be some of the finest quality rifle brass, and all things being equal, it's the author's opinion that you will get more reloads out of Lapua brass than some other brands, (e.g., Remington brass).

- Brass loaded at a relatively low velocity will typically handle more reloads than brass loaded at relatively high velocities for any given caliber. For example, all things being equal, .308 / 7.62x51mm rounds loaded to a velocity of 2550fps will generally allow for more reloads than cartridges loaded to 2850fps.

- Full length sizing dies “work” the brass relatively more than neck sizing dies, which again, with all things being equal can result in relatively fewer reloads. One might ask what does “working” the brass mean? Prior to firing, the brass case is actually smaller than the chamber that the cartridge in which it is seated, and when the cartridge is ignited the explosive force inside the brass causes the casing to expand to fill the chamber. When using a full length sizing die, the die takes the expanded case and shrinks it back to the SAAMI specifications. With each loading and firing this stress is repeated, which over time takes a toll on the brass.With a neck sizing die, after the cartridge is fired in the chamber where, again, it is formed to the chamber of that particular rifle ("fire forming"), the sizing process only impacts the neck, which is resized to SAAMI specifications. The rest of the case is left to the dimensions of the particular chamber in which it was fired. There are pros and cons to both types of sizing dies, but that discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

- Primer pockets can also become “loose,” which means that the primers sit loosely in the pocket and can even fall out on occasion. Short of the primer falling out, gas can escape around the primer. This is often seen as carbon build-up around the loose primer.

- Finally, each time a particular piece of brass is fired, the neck hardens ever so slightly. Over time the neck gets so hard that it affects the ability to maintain a consistent neck tension and will sometimes result in split necks. This can sometimes be prevented by "annealing," which is a heat treating process used to return the necks to a less-brittle or less-hardened state.

In conclusion, the best procedure used to find out how many firings you can expect is to fire your brass in batches. A batch is a set of brass of the same, single headstamp, loaded to the same charge and fired the same number of times in the same gun. You should keep your once fired brass, five times fired brass and nine times fired brass, etc. separate. Take one batch of brass, reload and shoot it repeatedly, maintaining a record of the number of firings until you start to see evidence of thinning cases and/or other signs of weakened or suspect brass. That number of firings (less one) is the number of times you can expect to safely reload and shoot that brand of brass, with that particular load, in your particular rifle.